There are people who do not like MPEG (I wonder why), but so far I have not found anybody disputing the success of MPEG. Some people claim that only a few MPEG standards are successful, but maybe that is because some MPEG standards are_so_ successful.

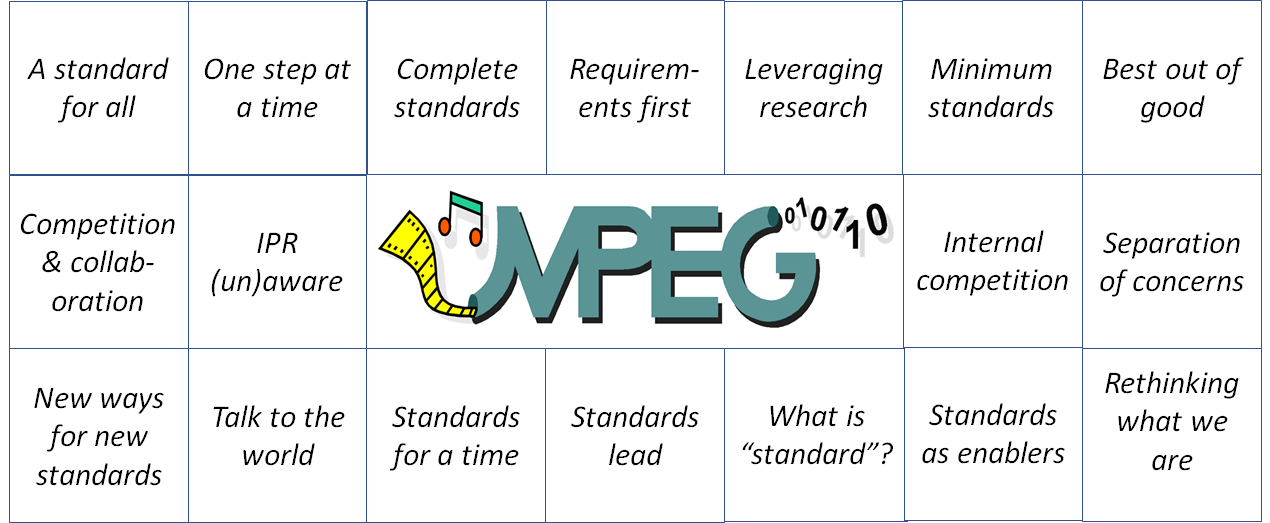

In this article the reasons of MPEG success are identified and analysed by using the 18 elements of the figure below.

A standard for all. In the late 1980’s many industries, regions and countries had understood that the state of digital technologies justified the switch from analogue to digital (some acted against that understanding and paid dearly for it). At that time several companies had developed prototypes, regional initiatives were attempting to develop formats for specific countries and industries, some companies were planning products and some standards organisations were actually developing standards for their industries. The MPEG proposal of a generic standard, i.e. a common technology for all industries, caught the attention because it offered global interoperability, created a market that was global – geographically and across industries – and placed the burden of developing the very costly VLSI technology on a specific industry accustomed to do that. The landscape today has changed beyond recognition, but today the revolutionary idea of that time is taken as a matter of fact.

One step at a time. Even before MPEG came to the fore many players were trying to be “first” and “impose” their early solution on other countries or industries or companies. If the newly-born MPEG had proposed itself as the developer of an ambitious generic standard digital media technology for all industries, the proposal would have been seen as far fetched. So, MPEG started with a moderately ambitious project: a video coding standard for interactive applications on digital storage media (CD-ROM) at a rather low bitrate (1.5 Mbit/s) targeting the market covered by the video cassette (VHS/Beta). Moving one step at a time has been MPEG policy for all its subsequent standards.

Complete standards. In 6 months after its inception MPEG had already realised the obvious, namely that digital media is not just video (although this it the first component that catches the attention), but it is also audio (no less challenging and with special quality requirements). In 12 months it had realised that bits do not flow in the air but that a stream of bits needs some means to adapt the stream to the mechanism that carries it (originally the CD-ROM). If the transport mechanism is analogue (as was 25 years ago and, to large extent, still today), the adaptation is even more challenging. Later MPEG also realised that a user interacts with the bits (even though it is so difficult to understand what exactly is the interaction that the user wants). With its MPEG-2 standard MPEG was able to provide the industry with a complete Audio-Video-Systems (and DSM-CC) solution whose pieces could also be used independently. That was possible because MPEG could attract, organise and retain the necessary expertise to address such a broad problem area and provide not just a solution that worked, but the best that technology could offer at the time.

Requirements first. Clarifying to yourself the purpose of something you want to make is a rule that should apply to any human endeavour. This rule is a must when you are dealing with a standard developed by a committee of like-minded people. When the standard is not designed by and for a single industry but by many, keeping this rule is vital for the success of the effort. When the standard involves disparate technologies whose practitioners are not even accustomed to talk to one another, complying with this rule is a prerequisite. Starting from its early days MPEG has developed a process designed to achieve the common understanding that lies at the basis of the technical work to follow: describe the environment (context and objectives), single out a set of exemplary uses of the target standard (use cases), and identify requirements.

Leveraging research. In the late 1980s compression of video and audio (and other data, e.g. facsimile) had been the subject of research for a quarter of a century, but how could MPEG access that wealth of technologies and know-how? The choice was the mechanism of Call for Proposals (CfP) because an MPEG CfP is open to anybody (not just the members of the committee) – see How does MPEG actually work? All respondents are given the opportunity to present their proposals that can, at their choice, address individual technologies, subsystems or full systems, and defend them (by becoming MPEG member). MPEG does not do research, MPEG uses the best research results to assemble the system specified in the requirements that always accompany a CfP. Therefore MPEG has a symbiotic relationship with research. MPEG could not operate without a tight relationship with research and research would certainly lose a big customer if that relationship did not exist.

Minimum standards. Industries can be happy to share the cost of an enabling technology but not at the cost of compromising their individual needs. MPEG develops standards so that the basic technology can be shared, but it must allow room for customisation. The notion of Profiles and Level provides the necessary flexibility to the many different users of MPEG standards. With profiles MPEG defines subsets of the general interoperability, with levels it defines different levels of performance within a profile. Further, by restricting standardisation to the decoding functionality MPEG extends the life of its standards because it allows industry players to compete on the basis of their constantly improved encoders.

Best out of good. When the responses to a CfP are on the table, how can MPEG select the best from the good? MPEG uses five tools:

- Comprehensive description of the technology proposed in each response (no black box allowed)

- Assessment of the performance of the technology proposed (e.g. subjective or objective tests)

- Line-up of aggressive “judges” (meeting participants, especially other proponents)

- Test Model assembling the candidate components selected by the “judges”

- Core Experiments to improve the Test Model.

By using these tools MPEG is able to provide the best standard in a given time frame.

Competition & collaboration. MPEG favours competition to the maximum extent possible. Many participants in the meeting are actual proponents of technologies in response to a CfP and obviously keen to have their proposals accepted. Extending competition beyond a certain point, however, is counterproductive and prevents the group from reaching the goal with the best results. MPEG uses the Test Model as the platform that help participants to collaborate by improving different areas of the Test Model. Improvement are obtained through

- Core Experiments, first defined in March 1992 as “a technical experiment where the alternatives considered are fully documented as part of the test model, ensuring that the results of independent experimenters are consistent”, a definition that applies unchanged to the work being done today;

- Reference Software, which today is a shared code base that is progressively improved with the addition of all the software validated through Core Experiments.

IPR (un)aware. MPEG uses the process described above and seeks to produce the best performing standards that satisfy the requirements independently of the existence of IPR. Should an IPR in the standard turn out not to be available, the technology protected by that IPR should be removed. Since only the best technologies are adopted and MPEG members are uniquely adept at integrating them, industry knows that the latest MPEG standards are top of the range. Of course one should not think that the best is free. In general it has a cost because IP holders need to be remunerated. Market (outside of MPEG) decides how that can be achieved.

Internal competition. If competition is the engine of innovation, why should those developing MPEG standards be shielded from it? The MPEG mission is not to please its members but to provide the best standards to industry. Probably the earliest example of this tenet is provided by MPEG-2 part 3 (Audio). When backward compatibility requirements did not allow the standard to yield the performance of algorithms not constrained by compatibility, MPEG issued a CfP and developed MPEG-2 part 7 (Advanced Audio Codec) that eventually evolved and became the now ubiquitous MPEG-4 AAC. Had MPEG not made this decision, probably we would still have MP3 everywhere, but no other MPEG Audio standards. MPEG values all its standards but cannot afford not to provide the best technology to those who demand it.

Separation of concerns. Even for the purpose of developing its earliest standards such as MPEG-1 and MPEG-2, MPEG needed to assemble disparate technological competences that had probably never worked together in a project (with its example MPEG has favoured the organisational aggregation of audio and video research in many institutions where the two were separate). To develop MPEG-4 (a standard with 34 parts whose development continues unabated), MPEG has assembled the largest ever number of competences ranging from audio and video to scene description, to XML compression, to font, timed text and many more. MPEG keeps competences organisationally separate in different in MPEG subgroups, but retains all flexibility to combine and deploy the needed resources to respond to specific needs.

New ways for new standards. MPEG works at the forefront of digital media technologies and it would be odd if it had not innovated the way it makes its own standard. Since its early days, MPEG has made massive use of ad hoc groups to progress collaborative work, innovated the way input and output documents are shared in the community and changed the way documents are discussed at meetings and edited in groups.

Talk to the world. Using extreme words, MPEG does have an industry of its own. It only has the industry that develops the technologies used to make standards for the industries it serves. Therefore MPEG needs to communicate its plans, the progress of its work and the results achieved more actively than other groups. See MPEG communicates the many ways MPEG uses to achieve this goal.

Standards are for a time. Digital media is one of the most fast evolving digital technology areas because most of the developers of good technologies incorporated in MPEG standards invest the royalties earned from previous standards to develop new technologies for new standards. As soon as a new technology shows interesting performance (which MPEG assesses by issuing Calls for Evidence – CfE) or the context changes offering new opportunities, MPEG swiftly examines the case, develops requirements and issues CfPs. For instance this has happened for its many video and audio compression standards. A paradigmatic case of a standard addressing a change of context is MPEG Media Transport (MMT) that MPEG designed having in mind a broadcasting system for which the layer below it is IP, unlike MPEG-2 Transport Stream, originally designed for a digitised analogue channel (but also used today for transport over IP as in IPTV).

Standards lead. When technology moves fast, as in the case of digital media, waiting is a luxury MPEG cannot afford. MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 were standards whose enabling technologies were already considered by some industries and MPEG-4 (started in 1993) was a bold and successful attempt to bring media into the IT world (or the other way around). That it is no longer possible to wait is shown by MPEG-I, a challenging undertaking where MPEG is addressing standards for interfaces that are still shaky or just hypothetical. Having standard that lead as opposed to trail, is a tough trial-and-error game, but the only possible game today. The alternative is to stop making standards for digital media because if MPEG waits until market needs are clear, the market is already full of incompatible solutions and there is no room left for standards.

Standards as enablers. An MPEG standard cannot be “owned” by an industry. Therefore MPEG, keeping faith to its “generic standards” mission, tries to accommodate all legitimate functional requirements when it develops a new standard. MPEG assesses each requirement for its merit (value of functionality, cost of implementation, possibility to aggregate the functionality with others etc.). Ditto if an industry comes with a legitimate request to add a functionality to an existing standard. The decision to accept or reject a request is only driven by a value substantiated by use cases, not because an industry gets an advantage or another is penalised.

What is “standard”? In human societies there are laws and entities (tribunals) with the authority to decide if a specific human action conforms to the law. In certain regulated environments (e.g. terrestrial broadcasting in many countries) there are standards and entities (authorised test laboratories) with the authority to decide if a specific implementation conforms to the standard. MPEG has neither but, in keeping with its “industry-neutral” mission, it provides the technical means – tools for conformance assessment, e.g. bitstreams and reference software – for industries to use in case they want to establish authorised test laboratories for their own purposes.

Rethinking what we are. MPEG started as a “club” of Telecommunication and Consumer Electronics companies. With MPEG-2 the “club” was enlarged to Terrestrial and Satellite Broadcasters, and Cable concerns. With MPEG-4, IT companies joined forces. Later, a large number of research institutions and academia joined (today they count for ~25% of the total membership). With MPEG-I, MPEG faces new challenges because the demand for standards for immersive services and applications is there, but technology immaturity deprives MPEG of its usual “anchors”. Thirty years ago MPEG was able to invent itself and, subsequently, to morph itself to adapt to the changed conditions while keeping its spirit intact. If MPEG will be able to continue to do as it did in the last 30 years, it can continue to support the industry it serves in the future, no matter what will be the changes of context.

I mean, if some mindless industry elements will not get in the way.

Suggestions? If you have comments or suggestions about MPEG, please write to leonardo@chiariglione.org.

Posts in this thread (in bold this post)

- Why is MPEG successful?

- MPEG can also be green

- The life of an MPEG standard

- Genome is digital, and can be compressed

- Compression standards and quality go hand in hand

- Digging deeper in the MPEG work

- MPEG communicates

- How does MPEG actually work?

- Life inside MPEG

- Data Compression Technologies – A FAQ

- It worked twice and will work again

- Compression standards for the data industries

- 30 years of MPEG, and counting?

- The MPEG machine is ready to start (again)

- IP counting or revenue counting?

- Business model based ISO/IEC standards

- Can MPEG overcome its Video “crisis”?

- A crisis, the causes and a solution

- Compression – the technology for the digital age

- On my Charles F. Jenkins Lifetime Achievement Award

- Standards for the present and the future