To get an explanation of the question in the title and an answer, the reader of this article should read the first 5 chapters. If in a hurry, the reader can jump here.

- MPEG is synonym of growth

- Manage growth with organisation

- MPEG does not only make, but “sells” standards

- A different approach to standards

- Interoperability is not just for commercials

- Time to answer the question

MPEG is a unique group in the way it has grown to what it is today. Thirty-one years ago it started as an experts group for video coding for interactive applications on compact disc (it became a working group only 3.4 years after its establishment). A few months after its establishment it added audio coding and systems aspects related to the handling of compressed audio and video. Two years later it moved to digital television (MPEG-2) shedding the “interactive applications on compact disc” attribute, and then it moved to audio-visual applications for the nascent fixed and mobile internet (MPEG-4), then to media delivery in heterogeneous environments (MPEG-H), then to media delivery on the unreliable internet (MPEG-DASH), then to immersive media (MPEG-I), then to genome compression (MPEG-G).

The list of MPEG projects given above is a heavily subsampled version of all MPEG projects (21 in total). However, it gives a clear proof of the effectiveness of the MPEG policy to extend to and cover fields that are related to compression of media. Now MPEG is even working on DNA read compression and has already approved 3 parts of the MPEG-G standard.

The MPEG story, however, is not really in line with the ISO policy on Working Groups (WG). WGs are supposed to be established and run like projects, i.e. disbanded after the task has been achieved. MPEG, however, has been in operation for 31 years because the field of standards for moving pictures and audio is far from being exhausted.

Today MPEG standards cover the following domains: Video Coding, Audio Coding, 3D Graphics Coding, Font Coding, Digital Item Coding, Sensors and Actuators Data Coding, Genome Coding, Neural Network Coding, Media Description, Media Composition, Systems support, Intellectual Property Management and Protection (IPMP), Transport, Application Formats, Application Programming Interfaces (API), Media Systems, Reference implementation and Conformance.

Manage growth with organisation

The MPEG story is also not really in line with another ISO policy on WGs. WGs are supposed to be “limited in size”. However, MPEG counts 1500 experts registered and an average 500 experts attending its quarterly meetings, These last one weeks and are preceded by almost another week of joint video projects and ad hoc group meetings.

The size of MPEG, however, is not the result of a deliberate will to be outside of the rules. It is the natural result of the expansion of its programme of work.

Since the early days, MPEG had a structure: first a Video subgroup, then an Audio subgroup, then a Systems subgroups. The Test subgroup was formed because there was a need to test the submissions in response to the MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 Video Calls for Proposals, the Requirements subgroup came with the need to manage the requirements of all industries interested in MPEG-2 and the 3D Graphics subgroup came with MPEG-4. The Communication subgroup came later prompted by the need to have regular communication with the outside world.

The MPEG organisation is not the traditional hierarchical organisation. Inside most subgroups there are units – permanent or established on an as needed basis – that address specific areas. Units report to subgroups but interact with other units, inside or outside their subgroups, prompted by a group that includes all subgroup chairs.

This unique flat organisation allows MPEG’s 500 experts to work on multiple projects, while allowing those interested in specific one to stay focussed. At the last October 2019 meeting experts worked on 60 parallel activity tracks and produced ~200 output documents. This is also possible because, since 1995, MPEG has been using a sophisticated online document management system now extended to make available information on other parallel meetings, to support the development of plenary results, to manage the MPEG work plan etc.

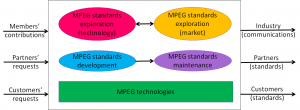

MPEG not only makes, but “sells” standards

Formally MPEG was not the result of a conscious decision by National Bodies (eventually it became so) but it was prompted by a vision. Therefore, MPEG never had a “guaranteed market”: its standards had to “sell” for MPEG to continue to exist. For that to happen, MPEG standards had to be perfectly tuned to market needs. In other words there had to be a closed relationship between supplier (MPEG) and customers (industries).

Therefore, searching for and listening to customers is in the MPEG DNA:

- For its first MPEG-1 standard MPEG found as customers consumer electronics (interactive video on compact disc and eventually Video CD), telcos (video distribution on ADSL-1), radio broadcasters (digital audio broadcasting). MP3 is a different story…

- For its MPEG-2 standard MPEG had to convince all types of broadcasters – terrestrial, cable and satellite – all consumer electronics companies and the first IT companies

- For its MPEG-4 standard MPEG has to convince the first wave of IT companies and to start talking to mobile communication companies

- And so on… Every new subsequent MPEG project brought some new companies of existing industries or new industries.

Above I have used the verb “brought”, but this is not the right verb, certainly not in the early years. MPEG made frenetic efforts to talk to companies, industry fora and standards organisations, presented its plans and sought requirements for its standards. The result of those efforts is that today MPEG can boast a list of several tens of major industry fora and standards organisations such as (in alphabetic order): 3GPP, ATSC, DVB, EBU, SCTE, SMPTE and more.

A different approach to standards

This intense customer-oriented approach is not what other JTC 1 committees do. If you want to build Internet of Things (IoT) solutions and you turn to standards produced by JTC 1/SC 41 – Internet of Things and related technologies, you are likely to only find models and frameworks. If you want to implement a Big Data solution and you turn to JTC 1/SC 42 – Artificial intelligence, you will find again models and frameworks but no trace of API, data formats or protocols.

Both MPEG and other JTC 1 subcommittees develop standards before industry has a declared need for them. However, they differ in what they deliver: implementable standards (MPEG) vs models and frameworks (other committees).

MPEG commits resources to develop specifications when implementation technologies may not be fully developed. Therefore, MPEG can assemble and possibly improve its specifications by adding more technologies to the extent it can be shown that they provide measurable technical merits.

The danger is that MPEG may very well spot the right standard, but its development may happen too early with the risk that the standard may be superseded by a better technology at the time industry really needs the standard. Conversely, the standard may arrive too late, at a time when companies have made real investments for their own solutions and are not ready to discount their investments.

This is one reason why, within JTC 1, MPEG (a WG) has produced more standards than any other subcommittee (note that a subcommittee includes several WGs). MPEG’s policy is to try and develop a new “business” area with a standard that may turn out not to be adopted by industry, not to risk losing an opportunity.

By providing models and frameworks, other committees take the approach of creating an environment where industry players share some basic elements on top of which an ecosystem of solutions with certain degrees of interoperability may eventually and gradually appear.

It is very difficult to make general comparisons, but it is clear that MPEG standards create markets because industry knows how to make products and users know they buy products that provide full interoperability. A proof of this? In 2018 MPEG-enabled devices had a global market value in excess of 1 T$ and MPEG-enabled services generated global revenues in excess of 500 B$. In the same year MPEG standards had a far reaching impact on people at the global level: at the global level there are 2.8 billion smartphones of which 1,56 billions were sold in 2018 alone (see here) and there are ~1.6 billion TV sets in global use by ~1.42 billion households serving a TV viewing audience of ~4.2 billion in 2011 (see here).

Interoperability is not just for commercials

MPEG is also unique because it has succeeded in converting what would otherwise be a naïve approach to interoperability to a practical and effective implementation of this notion. Back in 1992 MPEG was struggling with a problem created by the success of its own marketing efforts: many industries from many countries and regions had believed in the MPEG promise of a single international standard for audio and video compression, but actually industries and countries or regions had different agendas. Telcos wanted a scalable video coding solution, American broadcasters wanted digital HDTV, European broadcasters wanted digital TV scalable to higher resolutions, some industries sought a cheap solution (RAM was an important cost element at that time) while others could afford more expensive solutions.

The solution was obvious but making a standard that included all requirements for all users was out of question. MPEG learned from the notion of profile developed by JTC 1/SC 21 – Open systems interconnection (OSI):

“set of one or more base standards, and, where applicable, the identification of chosen classes, subsets, options and parameters of those base standards, necessary for accomplishing a particular function”

MPEG madeit practically implementable for its own purposes by interpreting “base standards” and “chosen classes, subsets, options and parameters of those base standards” as “coding tools”, e.g. a type of prediction or quantisation. Starting from MPEG-2 (but actually the profile and level notion – at that time not crystal clear yet – was already present in MPEG-1) MPEG standards conceptually specify collections of tools and descriptions of different combinations of tools, i.e. the “profiles”.

Next to quality, profile is the feature that has contributed the most to the success of MPEG standards. Today, OSI profiles are nowhere to be seen, but the world is full of products and services that implement MPEG profiles.

I will try now to give a meaning to “it” in the question of the title of this article “Which company would dare to do it?”

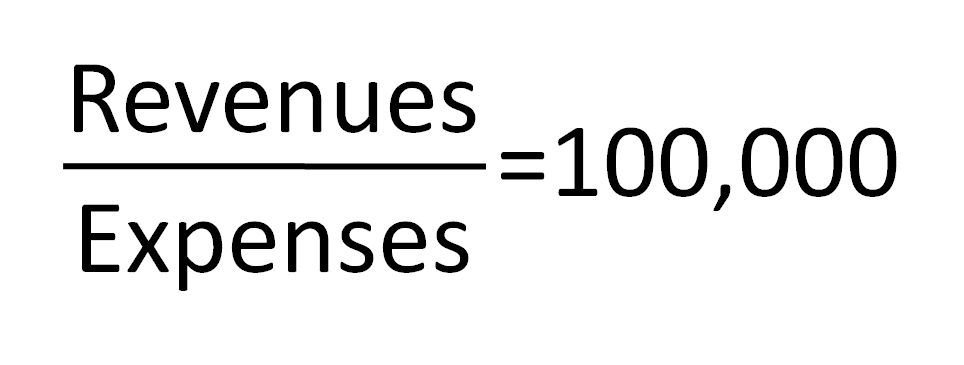

MPEG is a standards group, not a company. Still MPEG operates like a company: it produces standards to maximise the number of its customers by satisfying their needs. The measure of MPEG performance used here would probably not satisfy the criteria of an accountant, but I consider enabling a market of 1.5 T$ p.a. to be something akin to “profits” while expenses can be measured to be 500 (experts)*4 (meetings/year)*7.5 (meeting days)*1000 ($/day) = 15 M$.

What would you think of board of directors who wanted to reorganise a “company” whose Operating Expense Ratio (OER) is 0.001% (or its Revenues/Expenses ratio is 100,000)?

Posts in this thread

- Which company would dare to do it?

- The birth of an MPEG standard idea

- More MPEG Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats

- The MPEG Future Manifesto

- What is MPEG doing these days?

- MPEG is a big thing. Can it be bigger?

- MPEG: vision, execution,, results and a conclusion

- Who “decides” in MPEG?

- What is the difference between an image and a video frame?

- MPEG and JPEG are grown up

- Standards and collaboration

- The talents, MPEG and the master

- Standards and business models

- On the convergence of Video and 3D Graphics

- Developing standards while preparing the future

- No one is perfect, but some are more accomplished than others

- Einige Gespenster gehen um in der Welt – die Gespenster der Zauberlehrlinge

- Does success breed success?

- Dot the i’s and cross the t’s

- The MPEG frontier

- Tranquil 7+ days of hard work

- Hamlet in Gothenburg: one or two ad hoc groups?

- The Mule, Foundation and MPEG

- Can we improve MPEG standards’ success rate?

- Which future for MPEG?

- Why MPEG is part of ISO/IEC

- The discontinuity of digital technologies

- The impact of MPEG standards

- Still more to say about MPEG standards

- The MPEG work plan (March 2019)

- MPEG and ISO

- Data compression in MPEG

- More video with more features

- Matching technology supply with demand

- What would MPEG be without Systems?

- MPEG: what it did, is doing, will do

- The MPEG drive to immersive visual experiences

- There is more to say about MPEG standards

- Moving intelligence around

- More standards – more successes – more failures

- Thirty years of audio coding and counting

- Is there a logic in MPEG standards?

- Forty years of video coding and counting

- The MPEG ecosystem

- Why is MPEG successful?

- MPEG can also be green

- The life of an MPEG standard

- Genome is digital, and can be compressed

- Compression standards and quality go hand in hand

- Digging deeper in the MPEG work

- MPEG communicates

- How does MPEG actually work?

- Life inside MPEG

- Data Compression Technologies – A FAQ

- It worked twice and will work again

- Compression standards for the data industries

- 30 years of MPEG, and counting?

- The MPEG machine is ready to start (again)

- IP counting or revenue counting?

- Business model based ISO/IEC standards

- Can MPEG overcome its Video “crisis”?

- A crisis, the causes and a solution

- Compression – the technology for the digital age